The “Basileion” (palace) of Aigai

The ‘Basileion’ (palace) of Aigai

The “Basileion” (palace) of Aigai

«θέμις δ’ οὔτ’ ἦν οὔτ’ ἔστιν τῷ ἀρίστῳ δρᾶν ἄλλο πλὴν τὸ κάλλιστον»

Plato, Timaeus 30a

“It was not and is not fair that the excellent should create anything but beauty”

The palace, the theater and the neighboring sanctuaries are elements of the great building program of Philip II (359-336 BC), who modernized and upgraded Aigai, the royal metropolis of the Macedonians, setting the ideological model for the cities of the Hellenistic Ekoumene. The monumental propylon that evokes a sanctuary, the impressive two-story arcades of the facade that open onto the city and invite citizens to make use of their space, the mega peristyle around which the banqueting areas are organized, the dome that, according to the inscriptions, was sanctuary of Herakles, the library/archive and the smaller western peristyle that served auxiliary uses (palaestra, etc.) show that the “basileion” of Aigai did not house the family and the private life of the king, but all those structures that were necessary for the exercise of multi-level public authority.

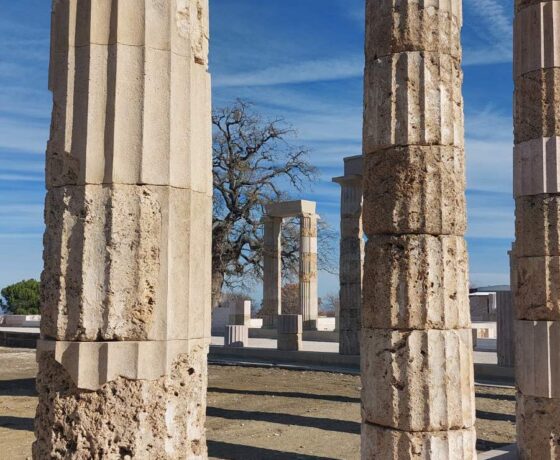

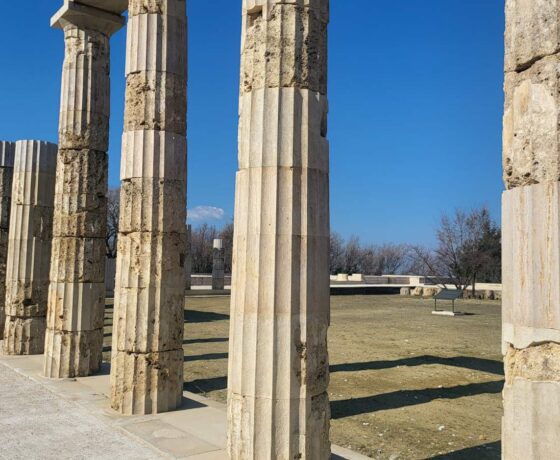

The palace, with the ancient name of the “Basileion” of Aigai, which with an area of approx. 15,000 m2 is the largest building in classical Greece, is a simple and functional building and at the same time monumental and imposing. The archetypal building is characterized by the luxury of the materials, the ingenuity and perfection of the execution, the unexpected achievements of technology that are detected at all levels, and at the same time by the geometric purity of the form that forms a set of incomparable tranquility, elegance and harmony, where all submit to the charm of the meter and are connected to each other by the Pythagorean ratio, the number φ 1.61 of the “golden ratio”.

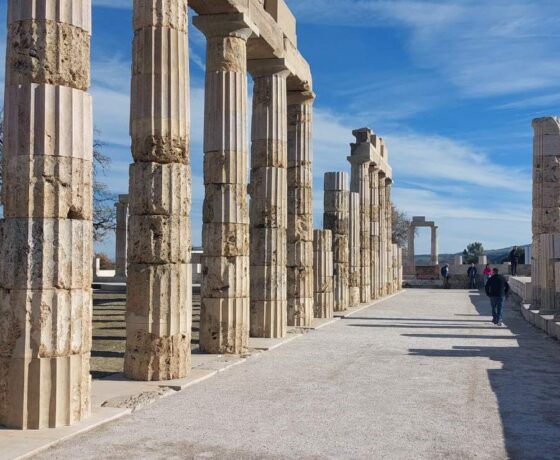

With 10 columns to the south and 11 to the north, the two arcades of the facade of the palace of Aigai were the first fully developed two-story arcades in Greek architecture, with Doric columns on the ground floor and Ionic amphibole columns on the first floor. Behind the south was a long hall, into which two doors led. The north portico was double. The extroversion and public character of the palace galleries are underlined by the desks that surrounded their walls and provided space for at least 120 people. Traces of a system of attaching wooden panels to the southern gallery allow the hypothesis that this was the place where laws and decrees were published, the place where the king exercised his judicial power, something like the “royal gallery” of Athens. In the north, which was more spacious, perhaps we should imagine philosophical presentations, discussions and teachings.

The extremely monumental propylon with the pediment, the volume of which protruded slightly, was clearly distinguished from the arcades by the interposition of the narrow walls. The autonomy of the propylon was underlined by the presence of the radian ionic double columns which are higher than the doric columns of the arcades and emphasize the element of height. From the interior of the propylon, two side doors led to the galleries. Two pairs of ionic double columns with corner capitals demarcate the passage towards the entrance, emphasizing the passage element. The pseudo-windows which exactly correspond to the dimensions of the relief openings above the metapilons of the propylon help to accurately represent the facade of its upper floor, the image of which is preserved in the “tomb of the Judgment” in neighboring Mieza.

Embedded in the array of spaces surrounding the peristyle, forming an indivisible unity with it, the large square hall, entered through the central gate, is the vestibule par excellence of the building, a waiting area with desks along the side walls. From here one passed into the huge square peristyle which is without a doubt the “heart of the building”. The square turns out to be a key element in the design of the building, which is not, however, a simplistic jumble of square spaces that open onto the portico of the peristyle. A key element for the organization of the building’s functions is the creation of tripartite complexes of two types: A. Smaller, inward-facing apartment, inscribed in a square, consisting of a rectangular vestibule and two square banquet rooms B. Large, monumental, outward-facing compartment with three large, orderly arranged, spaces, the middle one of which is open and communicates directly with the peristyle through a polystyle of three or five amphipessocolumns, forming the vestibule for the other two which are recognized as banquet areas.

In the huge three-part apartment on the west side are located the largest (hall area approx. 280 sq.m.) roofed areas without internal supports of the classical architecture. More than 500 people could be seated in the five-pillar vestibule. This space, flooded by the morning light coming in from the multi-pillared opening of the east-facing porch, probably functioned as a meeting room.

In the most luxurious tripartite complex on the south side the magnificent mosaic with flowers and daisies has been preserved, and the rapture of Europe mosaic has recently been identified, a subject that testifies to Philip’s intentions, on the eve of the great conflict with the king of Asia to present himself as the ruler of Europe. There are also four large independent menses that communicate directly with the peristyle, a corridor that leads to the northern exterior from where one could see the action in the theater, but also to gaze at the entire Macedonian basin and a large corridor that leads to the western peristyle. Two staircases led to the floor that existed only above the small tripartite complexes, the propylon and the arcades of the facade.

Next to the propylon, the sacred dome, the closed complex with the small menses and the archive recall the idea of the Prytaneion, but here the place of the Mother of the Gods was taken by Patroos Heracles, the Father of kings, a mortal son of god who defeated death with his Virtue.

The western peristyle, which was single-storey and lower and practically hidden behind the volume of the East, was designed from the beginning apparently with the aim of housing auxiliary uses, necessary to support the official-public function of the main palace.

With 16 doric columns on each side, the mega peristyle of Aigai which epitomizes the concept of the square, is the first of its kind. Having an area of 4,000 square meters, it could accommodate at least 8,000 people and could function as a gathering place for Macedonians. Thus the “sacred-political agora” acquires a complex architectural form. The gathering place of the citizens takes on the image of a courtyard and the word “court” becomes synonymous with the concept of royalty. Next to the theater, in the place of spiritual purification of the citizens, point of reference for the homeless, landmark and center of the public space, the palace of Aigai surprises us with the “democratic” of its structure, from which there is no exception and elevation, elements that generally characterize palatial architecture outside Macedonia. In the halls, in the galleries, in the peristyle, the Macedonian king is always on the same level as his partners, next to and among them, a first citizen, an enlightened ruler and not at all a tyrant.

Fusing in a highly inventive manner traditional elements and radical inventions and setting Platonic ideas in stone, the genius architect creates an unprecedented building, designed to become the architectural manifesto of the ideal state, the tangible formulation in space of the idea of enlightened hegemony. Thus is born a revolutionary and pioneering building for its time that will immediately find many imitators and will seal the course of sacred and secular, public and private architecture for many centuries.

The building began to be constructed in the middle of the 4th century and was completed in 336 BC, when Philip II, at the height of his omnipotence celebration, was assassinated as he entered the neighboring theater. Here Alexander III was proclaimed king of the Macedonians (Arrian, Al. A. 1.25.1 – 2 ) and began the course that would change the world.

In the years of the Antigonides (3rd century BC) the large southern portico was added and the palaestra of the western peristyle was reorganized, but in general the building retains its original form. A venerable and sacred symbol of the “enlightened” Macedonian kingship, the palace would be permanently destroyed in the middle of the 2nd century BC after the final overthrow of the kingdom by the Romans of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus in 148 BC. However, the two centuries of its existence were enough for it to emerge as a building – a norm and a model, a monumental archetype that will find many imitators and seal the course of sacred and secular, public and private architecture for many, many centuries …

(Angeliki Kottaridi)

τηλ. 23310 92347

For more info: http://aigai.gr/